What makes Word Heritage Areas special?

From the world’s largest coral reef system to vast, ancient rainforests, Australia boasts 20 internationally-significant natural areas. So special are these places they’ve been given legal protection by an international convention administered by the United National Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Formally known as World Heritage Properties, these places contain cultural and natural heritage considered to be of extraordinary value to humanity.

Climate threats to Australia's World Heritage Areas

Our research identified 17 of Australia’s 20 World Heritage Properties are likely to be impacted by climate change:

- Budj Bim Cultural Landscape

- Fossil Mammal Sites

- Gondwana Rainforests of Australia

- Great Barrier Reef

- Greater Blue Mountains

- Heard and MacDonald Islands

- Kakadu National Park

- Kgari (Fraser Island)

- Lord Howe Island

- Macquarie Island

- Ningaloo Coast

- Purnululu National Park

- Shark Bay

- Tasmanian Wilderness

- Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park

- Wet Tropics of Queensland, and

- Willandra Lakes Region.

Climate damage and the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area

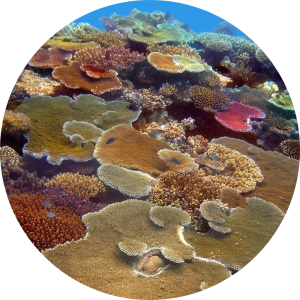

The Great Barrier Reef is an example of a World Heritage Area at risk of collapse from climate breakdown.

Visible from space and home to thousands of animal and plant species, the Great Barrier Reef is one of the world’s most magnificent natural wonders.

But climate change is already impacting the Reef, with warming oceans making mass coral bleaching events more frequent and severe. In 2016 and 2017, the Great Barrier Reef experienced consecutive occurrences of the most severe coral bleaching in recorded history.

Our research shows that concerns about the impacts of climate change on the Reef have been voiced repeatedly over the years in the Australian Government’s own reports to the World Heritage Committee, statements by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, and in IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessments (among other materials).1

Without vast and urgent cuts to emissions, coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef and other Australian coral reef systems is virtually certain.

Coral bleaching, Great Barrier Reef.

Photograph: Harriet Spark.

Climate-fuelled events like cyclones may also increase crown of thorn starfish outbreaks, killing coral in plague-like proportions and causing further damage to this great living system.

-

Read more evidence on climate risk to the Reef

The Australian Government’s report to the World Heritage Committee in 2019 identified climate change as the most serious and pervasive threat to the Reef. The report identified that the long term outlook for the Reef’s ecosystem had deteriorated from poor to very poor, and accelerated action to mitigate climate change was essential to turn around this outlook.2

The IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment for the Reef in 2020 identified climate change as the biggest threat to the long-term conservation of the Great Barrier Reef and its Outstanding Universal Value. The threat from ocean acidification, temperature extremes and storms/flooding was graded as a “very high threat.”3

-

Evidence of current climate impacts

The impact of climate change upon the Great Barrier Reef is also discussed extensively in IPCC WGII, which notes the Great Barrier Reef is already severely impacted by climate change, particularly ocean warming, through more frequent and severe coral bleaching (very high confidence). In 2016 and 2017, the Great Barrier Reef experienced consecutive occurrences of the most severe coral bleaching in recorded history. The 2016 bleaching event affected 90% of reefs.4

Increased heat exposure also affects the abundance and distribution of associated fish, invertebrates and algae (high confidence). Thus, coral bleaching is an indicator of thermal effects on coral habitat, fauna and flora.5

-

Predicted future climate impacts

Bleaching is expected to continue for the Great Barrier Reef, and Australia’s other coral reef systems (virtually certain).5

Increases in cyclone intensity projected for this century, and other extreme weather events, will greatly accelerate coral reef degradation. Extreme weather events may contribute to an increased frequency and/or amplitude of crown of thorn starfish outbreaks, further reducing the spatial distribution of coral.6

-

Endnotes

1 [84] Department of the Environment

and Energy, State Party Report on the State of Conservation of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (Australia) (2019), 3, 12. GBRMPA, Outlook Report 2014 (2014), v, 264. GBRMPA, Outlook Report 2019 (2019), v, 90, 185, 186, 257. IUCN, Great Barrier Reef: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

(finalised 2 December 2020), 5-6, 7.2 Department of the Environment and Energy, State Party Report on the State of Conservation of the

Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (Australia) (2019), 3, 12.3 IUCN, Great Barrier Reef: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 2 December 2020), 5-6, 7.

4 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-38.

5 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-38.

6 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-38.

Climate damage and the Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area

Another example of a World Heritage Area at grave risk from more climate damage is Queensland’s Wet Tropics.

Stretching across the north-east coast of Australia for some 450km, Queensland’s Wet Tropics are a living natural wonder and a cultural landscape like nowhere else on Earth. With abundant song birds and marsupials and an exceptional diversity of plants, this World Heritage Area is also home to a number of endangered species. The area also has exceptional natural beauty, with waterfalls and wild rivers, rugged gorges, and sweeping forests hugging the sea.

The Wet Tropics covers less than 0.2% of the Australian continent, but contains:

- 30% of our marsupial species

- 60% of bat species

- 25% of rodent species

- 40% of bird species

- 30% of frog species

- 20% of reptile species

- 60% of butterfly species

- 65% of fern species

- 21% of cycad species

- 37% of conifer species

- 30% of orchid species and

- 18% of Australia’s vascular plant species.

UNESCO notes the area is “therefore of great scientific interest and of fundamental importance to conservation.” According to its UNESCO listing, the area:

“…presents an unparalleled record of the ecological and evolutionary processes that shaped the flora and fauna of Australia, containing the relicts of the great Gondwanan forest that covered Australia and part of Antarctica 50 to 100 million years ago.”

Photograph: Endangered Southern Cassowary

(Casuarius casuarius johnsonii). Daintree rainforest,

Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area.

However our research shows the Wet Tropics of Queensland are particularly vulnerable climate change.

UNESCO notes that “a key emerging threat to the integrity of the property is climate change, as with even a small increase in temperature, large declines in the range size for almost every endemic vertebrate species confined to the property are predicted.”

-

Read more of evidence on climate risks to the Wet Tropics of Queensland

- The Wet Tropics are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change (IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessments in 2014, 2017 and 2020.)7

- Climate change will have severe effects on the Outstanding Universal Value of the site, particularly on animals with low temperature range tolerances and montane flora and fauna (The 2020 IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment)8

- Climate change is a major threat to the area’s biodiversity. Some keystone species are already critically endangered partly through climate change impacts (for example the spectacled flying fox from extreme temperature events), and cool adapted upland possum species and high altitude birds are being adversely impacted by existing changes in climatic conditions. (2020 IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment)9

Spectacled Flying-fox (Pteropus conspicillatus),

Endangered, Far North Queensland. -

Endnotes

7 IUCN, Wet Tropics of Queensland: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 2 December 2020)

8 IUCN, Wet Tropics of Queensland: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 2 December 2020)

9 IUCN, Wet Tropics of Queensland: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 2 December 2020)

Climate damage and Kakadu National Park World Heritage Area

Kakadu National Park is another example of a World Heritage Area at grave risk from climate breakdown.

The World Heritage listing for Kakadu describes it as a living cultural landscape with exceptional natural and cultural values. Of importance are its art sites, rock art and archaeological record, its vast expanse of Ramsar-listed wetlands which provides habitat for millions of waterbirds, its diversity of habitats, and its extensive and relatively unmodified natural vegetation and largely intact faunal composition.

With cave paintings, rock carvings and archaeological sites, it is a world-renowned record of its hunter-gatherers inhabitants from prehistoric times to the First Nations people still living in Kakadu.

The property protects an extraordinary number of plant and animal species including over one third of Australia’s bird species, one quarter of Australia’s land mammals and an exceptionally high number of reptile, frog and fish species. Huge concentrations of waterbirds make seasonal use of the park’s extensive coastal floodplains.

Photograph: Ramsar wetland Kakadu

National Park World Heritage Area.

However the evidence shows climate change is already detrimentally harming the site’s values, has the potential to impact almost all World Heritage values in the site.

-

Read more evidence on existing climate harm to Kakadu

Progressive saltwater intrusion into lowland wetlands as a result of climate change has already been observed and is having detrimental impacts on the site’s values.

Extreme weather events recently caused large scale losses of mangroves within the site and in the broader region. Saltwater intrusion will increasingly cause major changes in the composition, productivity, ecological dynamics and values of the site’s significant lowland wetland assemblages.

The presence of invasive plant species that cause a dramatic increase in the intensity of fire, and thus threaten many natural values, will worsen under warmer temperatures.

The overall assessment provided by the 2020 IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment states:

“Climate change is already having detrimental impacts on the site’s values, mostly through nascent saltwater intrusion. These impacts will increase in severity and consequences over coming decades, with marked detriment to the site’s biodiversity and cultural values.”

-

Predicted climate risks to Kakadu in the future

The 2020 IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment also states that climate change has the potential to affect almost all World Heritage values in the site.

The 2016-2026 Kakadu Management Plan notes a number of threats to World Heritage values arising from climate change, including:

- The “highly significant” threat of climate change on cultural sites in coastal and lowland areas through rising sea levels and saltwater inundation;

- The “highly significant” threat of sea-level rise on floodplain values, and of extreme weather events on coastal and riverine areas;

- The “highly significant” threat of invasive species that increase the intensity of fires, a threat which is likely to be exacerbated by climate change;

- Increased frequency and intensity of fire arising from a drier and hotter climate has implications for fire sensitive vegetation communities and for rainforest which comprises many species intolerant of fire.

-

Endnotes

10 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/147

11 IUCN, Kakadu National Park: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 8 December 2020), 9. Director of National Parks, Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026 (2016), 52; 68, 72, 92-93.

12 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/147

13 Director of National Parks, Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026 (2016), 52

14 Director of National Parks, Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026 (2016), 68.

15 Director of National Parks, Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026 (2016), 72

16 IUCN, Kakadu National Park: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 8 December 2020), 9.

17 IUCN, Kakadu National Park: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 8 December 2020), 9.

18 IUCN, Kakadu National Park: 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment (finalised 8 December 2020), 9.

19 Director of National Parks, Kakadu National Park Management Plan 2016-2026 (2016), 52, 68, 72, 92-3.