Why are ecological communities in Australia nationally significant?

An ecological community is a naturally occurring group of native plants, animals and other organisms that interact in a unique habitat, which is vital for their survival. In Australia, 91 woodlands, grasslands, shrublands, forests, wetlands, marine, ground springs and cave communities are threatened and listed under the EPBC Act.

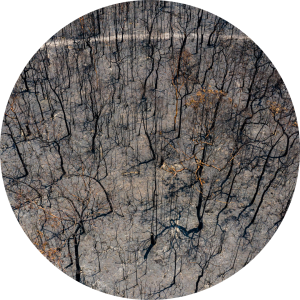

Photograph: Spotted-tail Quoll (Dasyurus maculatus), Endangered, Monga National Park, NSW. Not long after this photograph was taken, this area was badly burned in the Black Summer bushfires. Photographer: David Gallan.

Climate threats to nationally protected ecological communities

There are currently 91 threatened ecological communities in Australia listed under the EPBC Act. Of the 77 we reviewed, 66 are likely to be impacted by climate change.

The IPCC projects climate change will become an increasingly dominant stress on biodiversity in Australia, with many ecosystems experiencing irreversible changes and some threatened species going extinct.

Widespread and severe impacts on ecosystems and species are now evident across the Australasia region (very high confidence), with climate impacts reflecting both ongoing change and discrete extreme weather events.1

Fundamental shifts are observed in the structure and composition of some ecosystems, with impacts on species including global and local extinctions, severe regional population declines, and phenotypic responses.Climate change has synergistic and compounding impacts particularly in bioregions already experiencing ecosystem degradation, threatened endemics and collapse of keystone species.

In terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, land use impacts are interacting with climate, resulting in significant changes to ecosystem structure, composition and function, with some landscapes experiencing catastrophic impacts.

The 2019-2020 bushfires had significant consequences for wildlife and flow-on impacts for aquatic fauna.2

As to the future, climate change is projected to become an increasingly dominant stress on biodiversity, with some ecosystems experiencing irreversible changes in composition and structure and some threatened species becoming extinct (high confidence).3

Climate change will interact with current declines, heat-related mortalities, extinctions and disruptions for many species and ecosystems (high confidence). Some impacts observed to date may be irreversible where projected impacts on ecosystems and species persists.4

-

Endnotes

1 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19.

2 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-20.

3 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-22.

4 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19.

Climate risks for forest and woodland ecosystems of southern and southwestern Australia

Australia’s forests and woodlands are rich ecosystems that bind and nourish our ancient soils, sustain and shelter wildlife, and protects streams, wetlands and coastlines.

From the Jarrah-Karri forests in Southwest Australia Global Diversity Hotspot in WA to towering Mountain Ash forests in the East, our forests and woodlands are complex and extraordinary ecosystems.

However there is considerable evidence of climate change pressures on these ecosystems and species, and IPCC predictions for the future are serious.5

-

Evidence of current climate impacts

A range of forest and woodland types are already experiencing drought-induced canopy die-back – such as northern jarrah forests.6

In some areas, dominant canopy tree species are dying and being replaced by woody shrubs.

For some trees like Alpine Ash, seeders have insufficient time to reach reproductive age. For others, like Snow Gum woodlands, this is because vegetative regeneration capacity is exhausted.

Across our forests, fire-sensitive tree species are also dying from unprecedented fire events.7

Ancient Jarrah forest, Wellington

National Park near Collie Western Australia. -

Predicted future climate impacts

The IPCC projects future climate impacts will include an increase in fire frequency which will prevent recruitment of obligate seeders, and result in changing dominant species and vegetation structures, including long-lasting or irreversible shifts in formation from tall wet temperate eucalypt forests dominated by obligate seeder trees (e.g. Alpine Ash) to open forest or, worst case, to shrubland.8

In addition, the IPCC predicts declining rainfall and regolith drying will result in more unplanned, intense, fires and declining productivity places stress on tree growth and compromises biodiversity in the northern jarrah forest.9

It also predicts population collapse and severe range contraction of slow-growing, fire-sensitive paleoendemic temperate rainforests species.10

More detail on specific forest and woodland ecosystem communities in this region:

-

Endnotes

5 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

6 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

7 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

8 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

9 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

10 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

Climate risks and Australian alpine ecosystems

Australian alpine zones in the Alps and Tasmania are mountain ranges and tablelands that are home to abundant birdlife, insects, alpine vegetation and wildlife.

Despite their snow, these regions have already experienced a range of climate impacts, such as prolonged drought and intense alpine fires. Warming temperatures mean threatened species are losing snow-related habitat, as well as shifts in dominant vegetation patterns.11

-

Evidence of current climate impacts

Documented evidence of climate impacts on the Australian Alps bioregion and the Tasmanian alpine zones include shifts in dominant vegetation with a decline in grasses and other graminoids and an increase in forb and shrub cover in Bogong High Plains, Victoria.12

Bogong Moth (Agrotis infusa).

Photographer: Jean-Paul Ferrero.In addition, climate change has caused a loss of snow-related habitat for alpine zone endemic and obligate species.13

-

Predicted future climate impacts

For the future, the IPCC’s indicative selection of projected climate change impacts for Alpine ecosystems includes the loss of alpine vegetation communities and increased stress on snow-dependent plant and animal species, as well as changing suitability for invasive species.14

-

Endnotes

11 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-19, 24-25.

12 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-22.

13 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-22

14 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-25.

Climate risks and Australia's freshwater ecosystems

Another example of an ecosystem community under threat from climate damage is Australia’s freshwater ecosystems.

Although one of the driest continents on Earth, Australia’s aquatic ecosystems are home to a rich diversity of plants and animals. From lakes to rivers, wetlands to billabongs, ponds to swamps and bogs, our freshwater ecosystems are vital habitat for fish, turtles, frogs and invertibrates to feed, spawn and shelter.

However Australia’s freshwater ecosystems are already impacted by climate change, and climate predictions into the future are serious.15

-

Evidence of current and predicted future climate impacts

There is already documented evidence of mass mortality of freshwater fish (of which several are listed as threatened, such as the critically endangered Galaxia rostarus).16

In the Murray-Darling River Basin, climate change is predicted to cause reduced river flow and mass fish kills, which we have already seen.17

For 22 narrow range fish species, extinction is likely within the next 20 years. For freshwater taxa (freshwater fish, crayfish, turtles and frogs), substantial changes to the composition of faunal assemblages in Australian rivers are predicted well before the end of this century, with suitable habitat area predicted to decrease for many crayfish and turtle species and nearly all frog species (of which several are listed as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable.)18

Murray River Turtle (Emydura macquarii).

-

Endnotes

15 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-22.

16 Fishes that are Critically Endangered Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Species Profile and Threats Database (Web Page, 20 March 2022)

17 IPCC WGII, Chapter 11, p 11-25.

18 Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Frogs that are Critically Endangered; Frogs that are Endangered; Frogs that are Vulnerable. Species Profile and Threats Database (Web Page, 20 March 2022).